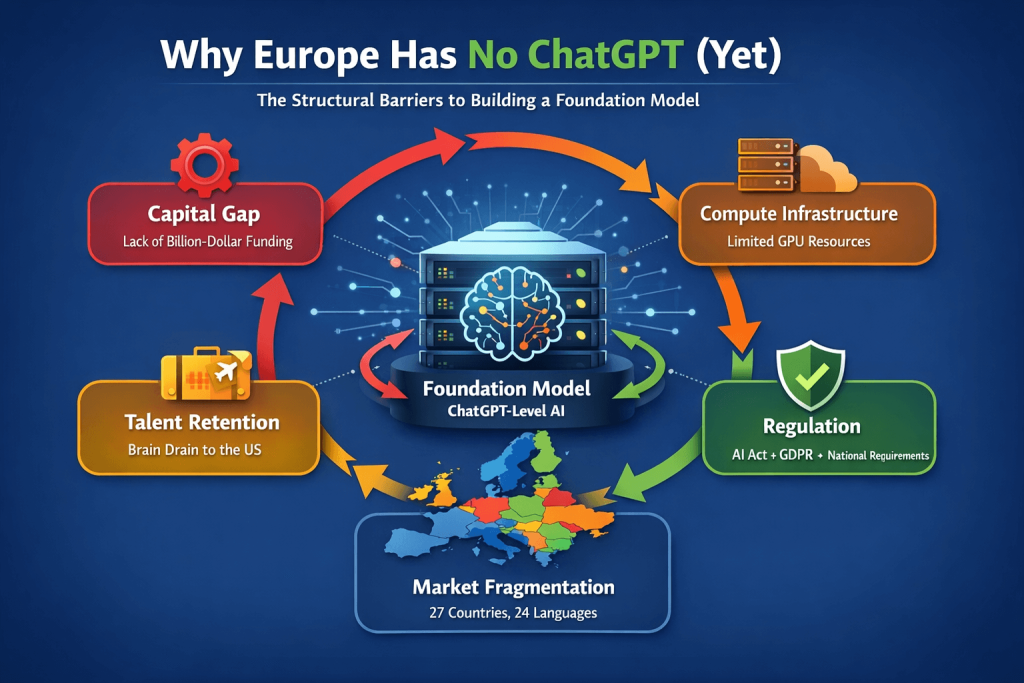

Europe does not have its own ChatGPT. And this is not due to a lack of talent or ambition. It is the result of structural conditions that have developed over many years — and cannot be resolved through a single funding program or political speech. Anyone seeking to understand why European AI alternatives are barely visible in the consumer market needs to look at five interconnected factors.

What “Alternative” Actually Means Here

Before discussing the causes, it helps to clarify terminology. Many tools promote themselves with labels such as “European AI” or “AI Made in Germany.” Most of these operate on the application layer — they rely on backend models from OpenAI, Anthropic, or Google while adding their own interface, privacy features, or industry-specific functionality.

That is not inherently bad. But it is fundamentally different from a foundation model: a large language model trained from the ground up with proprietary data, infrastructure, and research teams. ChatGPT is based on GPT-4o, such a foundation model. When this article refers to “real alternatives,” it means this level — not wrappers with an EU flag.

Capital: The Largest Structural Disadvantage

Developing a competitive foundation model requires resources on a scale that European financing structures rarely support. Since 2023, OpenAI has completed multiple multi-billion-dollar funding rounds. Google, Meta, and Microsoft invest tens of billions annually in AI infrastructure and research.

Europe’s VC landscape operates on a different scale. Individual funding rounds in the hundreds of millions are already exceptional. Mistral AI demonstrated this with its funding — and remains the exception rather than the rule. Additionally, European investors tend to be more risk-averse. The willingness to invest hundreds of millions into a company that may take years to become profitable is significantly stronger in the United States.

The result is a vicious cycle. Without massive funding, no world-class training. Without a world-class model, no compelling product. Without a compelling product, no users — and therefore no argument for the next funding round.

Compute Power and Cloud Infrastructure

Training foundation models means running thousands of GPUs in parallel for weeks or months. This computing capacity is almost entirely controlled by American hyperscalers — AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. European cloud providers such as OVHcloud or IONOS are strong in traditional hosting but do not offer comparable GPU infrastructure for AI training.

The EU has recognized this and launched programs such as EuroHPC to build European supercomputing capacity. These initiatives are a start. However, they primarily address the scientific domain and do not cover the commercial demand required to support multiple foundation model companies simultaneously. Today, anyone in Europe wanting to train a large language model will most likely rent GPU clusters from a US provider.

The Talent Market: Strong Education, Weak Retention

Europe’s universities and research institutions produce world-class AI research. DeepMind was founded in London. Yann LeCun studied in Paris. ETH Zurich, TU Munich, EPFL — educational quality is internationally competitive.

The problem lies not in training talent but in retaining it. US companies offer salaries and equity packages that European employers rarely match. Larger teams, faster career paths, and access to infrastructure that simply does not exist in the same form in Europe further reinforce this dynamic. Brain drain is not new, but in AI it is particularly pronounced because demand for specialists far exceeds supply.

Market Fragmentation: 27 Countries, No Unified Market

A US startup launching an English-language product immediately reaches a market of over 300 million people with a unified legal system, language, and business culture. A European startup faces 27 countries with different languages, regulations, and funding mechanisms.

The EU is a single market for goods. For digital products — especially AI applications subject to regulatory requirements — it is only partially unified. Funding programs are nationally fragmented. Procurement processes follow different logics. Even within the EU, data protection implementation requirements vary depending on national supervisory authorities. This makes scaling more expensive and slower than in the US or China.

| Topic | United States | European Union |

|---|---|---|

| Market access | One unified market, 330M+ people | 27 countries, fragmented market |

| Language | One language for one product launch | 24 official languages, localization required |

| Legal framework | One federal system, one set of rules | 27 national interpretations of EU law |

| Funding landscape | Multi-billion dollar rounds common | Rounds above €500M remain exceptional |

| Public funding | Centralized federal programs (DARPA, NSF) | Fragmented across national and EU programs |

| Procurement | Single federal procurement process | 27 different public procurement systems |

| Regulatory burden | Lighter, faster to market | AI Act + GDPR + national requirements |

| Talent retention | High salaries, equity packages, visa programs | Brain drain to US, lower compensation ceiling |

| Cloud infrastructure | Hyperscalers headquartered domestically | Dependent on US hyperscalers for GPU access |

| Time to scale | Launch once, scale immediately | Country-by-country rollout |

Regulation: Obstacle or Competitive Advantage?

The AI Act, GDPR, and various national regulations create a compliance framework that US startups do not have to navigate to the same extent. For a young company with limited resources, every additional regulatory requirement means less budget for product development.

At the same time, the counterargument has merit. Regulation can create a trust advantage. Companies that demonstrably operate in a GDPR-compliant manner have a clear edge in certain sectors — healthcare, finance, public administration — compared to US providers whose data processing only partially meets European standards.

The honest answer is that regulation is both. It slows the development of consumer products but establishes a foundation for trustworthy B2B applications. Anyone expecting Europe to produce a second ChatGPT will likely be disappointed. Those looking for sovereign AI solutions for regulated industries will increasingly find them here.

What Exists: Europe’s AI Landscape (as of 2025/2026)

Despite structural disadvantages, European companies developing their own foundation models do exist. The landscape is limited — but real.

Mistral AI (France) is the best-known European player. The company has released several proprietary models, including open-source variants, positioning itself as a powerful alternative to OpenAI with a focus on API access for developers and enterprises. Mistral secured Europe’s largest AI funding round and collaborates with major cloud providers. The consumer product (Le Chat) exists but is not the strategic focus.

Aleph Alpha (Germany) has deliberately specialized in the B2B and public sector markets. Instead of competing with ChatGPT in the consumer space, the company targets use cases in regulated industries with proprietary hosting and European data sovereignty. Its strategic repositioning in recent years illustrates a broader trend: success for European providers is more likely to come through specialization rather than mass-market competition.

In addition, smaller initiatives and open-source projects exist, for example from research institutions or EU-funded consortia. These are relevant for specific use cases but do not appear as consumer-facing products.

A comprehensive overview of European AI alternatives and specialized tools can be found here:

Does Europe Even Need Its Own ChatGPT?

Focus on building a one-to-one consumer clone driven by political narratives like digital sovereignty or strategic independence.

Focus on data processing, contractual control, dependency management, and risk-based architecture decisions.

This question is often answered reflexively with yes — digital sovereignty, strategic independence, European values. The arguments are valid. But they become misleading if they lead to demands for a one-to-one ChatGPT clone.

The more strategically relevant question is: where does Europe actually need its own models — and where is a sovereign application layer built on existing foundation models sufficient? For most enterprise applications, the critical factors are where data is processed, which contractual frameworks apply, and how dependency on individual providers is limited. This does not necessarily require a European foundation model, but rather a well-designed architecture.

The situation differs for security-critical applications — defense, intelligence services, critical infrastructure. Here, dependence on US models represents a genuine risk. In these areas, digital sovereignty at the model level is truly relevant. For the average business process, it is only partially so.

What European Companies Can Do Now

Waiting for a European ChatGPT is not a strategy. Four more pragmatic approaches are:

Use US models in a GDPR-compliant way. Several providers now offer European hosting and data processing agreements that meet GDPR requirements. OpenAI’s EU hosting options, Azure OpenAI Service with European data centers, and comparable offerings from Anthropic and Google make it possible to use powerful models within European regulatory frameworks.

Evaluate European providers for specialized use cases. Companies operating in regulated industries or requiring maximum data sovereignty should assess providers such as Mistral or Aleph Alpha. Their models are sufficiently powerful for many B2B applications and offer advantages in compliance and contractual design.

Avoid vendor lock-in. The AI landscape is evolving rapidly. Companies that bind themselves completely to a single provider today may face problems in two years if pricing, licensing terms, or performance shift. Abstraction layers and multi-provider architectures are advisable.

Build expertise instead of waiting. Companies experimenting with AI now — including with US models — gain experience that cannot easily be replicated later. The key question is less “which model” and more “which process benefits.”

More on practical implementation and an overview of concrete European alternatives can be found here

Conclusion

Europe is unlikely to produce its own ChatGPT in the short term. The reasons are structural: capital, infrastructure, talent retention, and market fragmentation interact and cannot be solved in isolation. European initiatives such as Mistral or Aleph Alpha demonstrate that building proprietary foundation models is possible — but with different priorities and market positioning than ChatGPT.

For companies, this means the better strategy is not waiting but sovereign use of existing models within European frameworks. With the right architecture, performance and compliance can be combined without relying on a European equivalent that is unlikely to emerge anytime soon.